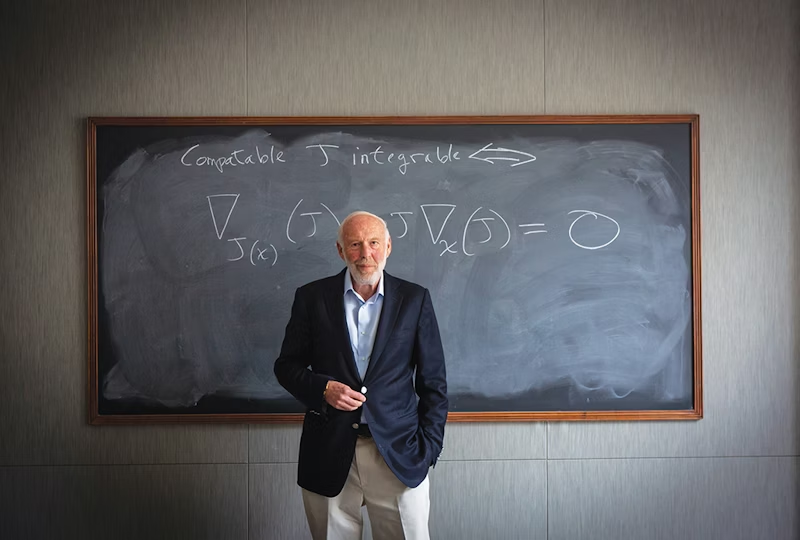

Remembering the Life and Careers of Jim Simons

Early Life and Mathematics

Jim Simons led a life driven by curiosity. Born in Newton, Massachusetts, on April 25, 1938, he showed an early affinity for mathematics. He’d pass the time by doubling numbers repeatedly and pondering Zeno’s paradox.

“I liked everything about math,” Simons said in a 2015 interview with the YouTube channel Numberphile. “The only thing I thought about was [that] I would be a mathematician.”

He went on to earn an undergraduate degree in mathematics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1958 and a doctorate in math from the University of California, Berkeley in 1961, at the age of 23. His thesis focused on differential geometry, the study of curved spaces such as manifolds, as would his later work. Between his two degrees, he and a friend from MIT rode motor scooters from Boston to Bogotá, Colombia, at times asking police if they could sleep in the relative safety and comfort of the local jail. (A request to which, surprisingly, the police frequently agreed.)

After earning his doctorate, Simons briefly taught at MIT and Harvard University before joining the Institute for Defense Analyses in Princeton, New Jersey. There, he worked as a code breaker for the National Security Agency, splitting his time between attacking cryptographic problems and continuing his own mathematics research.

In 1968, he was dismissed from the institute due to his public opposition to the Vietnam War, which included writing a letter to the editor of The New York Times in 1967 and later telling a Newsweek reporter that he’d stop working on Defense Department tasks until the war ended.

The dismissal wasn’t a setback for Simons. He quickly received an offer to head the mathematics department at the still relatively new Stony Brook University, part of the State University of New York system. There, he attracted talented mathematicians and established the department’s distinguished reputation.

“I knew then it was a top intellectual center with a serious commitment to research and innovation,” Simons said in 2023 following the historic $500 million donation he and Marilyn Simons made to Stony Brook’s endowment, the largest unrestricted gift to an American university in history. “Stony Brook also gave me a chance to lead — and so it has been deeply rewarding to watch the university grow and flourish even more.”

Simons continued to pursue his mathematical research at Stony Brook, collaborating most notably with Shiing-Shen Chern. Their paths had crossed briefly during Simons’ time at UC Berkeley, but at Stony Brook they were finally able to combine their talents.

“That was certainly the high spot of my mathematical life,” Simons said in a 2005 obituary for Chern in the Notices of the American Mathematical Society, “and I would think that anyone collaborating on a project with Chern would probably have said the same thing.”

Together, Simons and Chern published a paper in 1974 titled “Characteristic Forms and Geometric Invariants” that introduced geometric measurements called Chern-Simons invariants. Though the pair didn’t know it at the time, their work would play a seminal role not only in mathematics but in quantum field theory, string theory and condensed matter physics. In 1976, Simons received the American Mathematical Society’s Oswald Veblen Prize in Geometry for his mathematical research, including the discovery of Chern-Simons invariants.

“That work was good mathematics,” Simons said during a 2015 TED interview. “I was very happy with it; so was Chern. It even started a little subfield that’s now flourishing. Today, those things in there called Chern-Simons invariants have spread through a lot of physics. And it was amazing. We didn’t know any physics. It never occurred to me that it would be applied to physics. But that’s the thing about mathematics — you never know where it’s going to go.”

While at Stony Brook, Simons met Marilyn Hawrys. They shared a love of science and learning and married in 1977. Marilyn Simons earned her doctorate in economics from Stony Brook in 1984.

Revolutionizing Finance

Simons had always taken an interest in business, particularly finance. He traded stocks and dabbled in soybean futures during his time at UC Berkeley and was constantly on the lookout for investment opportunities. In 1978, he left academia to start Monometrics — renamed Renaissance Technologies in 1982 — in a strip mall just a stone’s throw from Stony Brook. After some false starts, the business quickly found a highly profitable approach: Apply mathematical modeling and other tools to trade investment products such as stocks, commodities and currencies.

Unlike other investment firms, Renaissance Technologies preferred to hire mathematicians, physicists and computer scientists rather than typical Wall Street types. Simons often described Renaissance Technologies’ top-tier scientists and collaborative atmosphere as the firm’s “secret sauce.”

“My management style has always been to find outstanding people and let them run with the ball,” he said in a 2017 New Yorker article.

A Passionate Philanthropist

Simons carried that approach into his philanthropic work as the Simons Foundation grew and evolved following its 1994 founding. In 2003, he and Marilyn Simons — who served as foundation president from its inception until July 2021 and now serves as chair — convened a roundtable of top neuroscientists and other experts to discuss autism research. That meeting led to the foundation’s first grantmaking program, the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI), and a sharpened focus on supporting mathematics and fundamental science.

“The remarkable thing about basic science — which includes mathematics — is that one never knows where it may lead,” Simons wrote in the 2019 Simons Foundation annual report. “Sometimes basic science seems to go nowhere, but more often it goes down a path leading to more discoveries, and more discoveries, and more discoveries. These often result in practical applications of which no one had dreamt, adding to the foundations of our civilization.”

As the foundation grew, Jim and Marilyn Simons expanded its grant programs to include biology, mathematics, physics, theoretical computer science, neuroscience, and science outreach and education. Foundation grantees have gone on to win Nobel Prizes, Fields Medals and other top honors, and the foundation’s scientific engagement efforts have been recognized with a Pulitzer Prize, an Academy Award nomination, and multiple Emmys and Peabody Awards.

After retiring as Renaissance Technologies’ chief executive officer in 2010, Simons became even more involved in and ambitious for the foundation’s work. In 2012, he and Marilyn Simons convened another seminal meeting, this time with experts from a variety of scientific fields. Out of this gathering came the idea for Simons Collaborations — programs that would bring together and support groups of outstanding scientists, often from different disciplines, to address topics of fundamental scientific importance, such as the inner workings of the brain and the origins of life.

The 2012 gathering also sparked the idea of establishing an institute dedicated to handling the flood of data generated by modern research and leveraging computing advances to drive scientific discovery. In 2016, the Simons Foundation realized this vision, establishing an in-house research division in New York City, the Flatiron Institute. The division has become a hub for computational science, with hundreds of researchers working on problems in astrophysics, biology, mathematics, neuroscience and quantum physics.

“We are proud to report that research emanating from Flatiron has been both copious and excellent, and the institute has acquired a great reputation in the United States and around the world,” Simons wrote in the 2018 Simons Foundation annual report.

In 2004, Simons founded a nonprofit organization committed to attracting and supporting outstanding math teachers in New York City schools. Named Math for America, the organization has since expanded to all STEM subjects in grades K-12, with 1,000 teachers receiving support each year — roughly 10 percent of the New York City STEM teaching force. Today, the organization serves as a model for similar efforts elsewhere in the United States.

“Instead of beating up the bad teachers, which has created morale problems all through the educational community, in particular in math and science, we focus on celebrating the good ones and giving them status,” Simons said during the 2015 TED interview.

During a 2010 talk at MIT, Simons set forth the five guiding principles that had shaped his life and careers in mathematics, investing and philanthropy. “Do something new; don’t run with the pack. Surround yourself with the smartest people you can find. Be guided by beauty. Don’t give up easily. Hope for good luck!”

We know that many people have stories, messages and memories they would like to share about Jim Simons. Please send them to observing@simonsfoundation.org.

Information on memorial services and other events honoring Jim’s life and legacy will be posted on the Simons Foundation website.