Mapping the Neural Circuits that Guide Worms to Reproduce

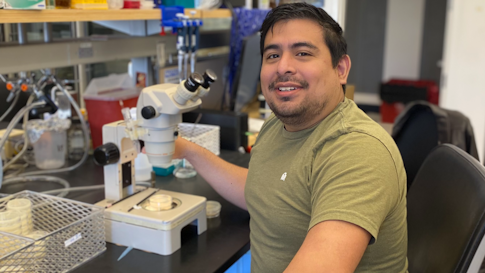

At one time in his life, Robert W. Fernandez was merely curious and observant about human nature and the different ways we behave, with no easy outlet for deeper academic pursuits. Fernandez had come to the United States during childhood as an undocumented immigrant, and he recalls he and his family having to face more immediate daily concerns. But as he worked to put himself through school, first at community college and then at the City University of New York (CUNY), Fernandez began to find opportunities that would set him on the path to a research career in neuroscience.

That path involved the completion of a doctoral degree at Yale University under the mentorship of biochemist Michael R. Koelle, followed by his current postdoctoral appointment at Columbia University in the lab of neuroscientist Oliver Hobert. In addition to his scientific research, Fernandez is the co-founder of Científico Latino, an organization that seeks to grow the pipeline of underrepresented students in the sciences.

Now in his second year as a Junior Fellow with the Simons Society of Fellows, Fernandez recently discussed both his scientific and his volunteer work with me. Our conversation has been edited for clarity.

What originally sparked your interest in neuroscience?

Growing up I was interested in questions related to our individuality, such as what makes us choose one path over another. But it was hard to study those questions in any great detail. Throughout my childhood and early on during college I had no opportunities to gain research experience; outside of classes, most of my time was spent working in a deli to help pay for school.

I originally enrolled in community college to study business administration. After two years, I moved to York College — part of CUNY — and shifted my studies to biotechnology. While at York I was given my first opportunity for research experience: to work in the lab of biology professor Anne F. Simon. She soon became one of my first mentors.

In Dr. Simon’s lab, we studied the neuroscience behind the social behavior of fruit flies. Previous research had shown that fruit flies exposed to other fruit flies that are experiencing stress may have shorter life spans. In our research, we studied the chemical mechanisms that help fruit flies learn to avoid this type of stressful social contact. This was my first chance to study the sorts of behavioral questions that had fascinated me since childhood. From that moment, I was hooked.

Tell us about your doctoral work.

At Yale I continued in the field of neuroscience but shifted my focus to the study of the roundworm C. elegans, a commonly studied model organism. Specifically, I wanted to gain a deeper understanding of the underlying neural circuitry behind the species’ ability to lay eggs.

At the time, much was known about this process, such as the fact that just four of C. elegans’ 302 neurons were involved in egg laying. We also knew which muscles were part of the egg-laying neural circuit, and that neurotransmitters such as serotonin played a key part in the process.

But there were still several unknowns. We did not know the exact role of the neurotransmitter receptors in egg laying or in which of the several types of egg-laying cells these receptors are found. The latter was our first question.

Undergraduate student Kimberly Wei and I underwent an ambitious task to map all 26 neurotransmitter receptors in the C. elegans egg-laying circuit. We discovered that a single neuron expresses around 14 receptors, which suggests that there may be a far greater amount of neurotransmitter signaling happening within these neural circuits than had been suggested by previous work.

We went on to investigate the function of these receptors in C. elegans’ egg-laying behavior and discovered that, while switching them off resulted in no detrimental changes, it was only by adding extra copies of the neurotransmitter receptors that we observed any severe egg-laying defects. This disparity indicated a high level of redundancy in the neural circuit, which underscored the importance of the system. We published this work in the Journal of Neuroscience in 2020.

What are you working on now as a postdoc at Columbia?

I am still working with C. elegans, but I am now trying to understand how a neuron develops its molecular identity — the suite of neurotransmitters, neuropeptides, receptors and other proteins that make one type of neuron different from another. I am particularly interested in the functions of proteins called homeodomain transcription factors, which are known to establish neuronal identity in C. elegans.

For my postdoc, I am focused on the male C. elegans nervous system. I want to know whether homeodomain transcription factors regulate the identity of male-specific neurons, and I am visualizing that by fluorescently tagging different transcription factors. This enables me to locate the neurons that are present within the C. elegans nervous system with a confocal microscope. In addition to studying how neurons are formed in the first place, I plan to explore in males how different neurons group themselves into neuronal circuits. The male C. elegans nervous system has been much less studied than the more popular hermaphrodite system (what I worked with during my doctorate), even though the male nervous system has more neurons and is somewhat more complex. My work aims to help close our knowledge gaps surrounding the male C. elegans nervous system and give us a better understanding of the biological processes of how neuronal circuits develop.

Switching gears, tell us about the mission of Científico Latino.

I have been fortunate to have great mentors, such as Dr. Simon, after arriving at CUNY and then later on during my education and training. They have all played pivotal roles in helping me find my current research path, and I am very grateful for that. Yet even with their guidance, I remember struggling sometimes to complete the necessary tasks that would set me up for success in graduate school and beyond — from how to narrow down the graduate programs that were right for me, to how to prepare a personal statement and CV.

When I began graduate school, I found others who were in similar positions; they had backgrounds like mine and were sometimes unsure how to navigate the process of applying to graduate school. After helping students with their graduate school applications informally a few times, I realized I could help more people if we set up an organization. In 2016, my friend Olivia Goldman and I co-founded Científico Latino with the goal of providing support to students who are underrepresented in science. We give practical coaching for those applying to graduate school. We also collect and curate information about available grants, scholarships and fellowships, and we set up every graduate school applicant with a mentor. I’m especially pleased, and honored, that some of those mentors are Simons Junior Fellows.

Finally, what are your thoughts about the Simons Junior Fellowship?

Throughout college and during graduate school, you are part of a research team and in the company of fellow students with whom you can connect.

Becoming a postdoc can often feel isolating at first, working primarily on your own projects and without the sense of community you had while in graduate school. The Simons Junior Fellowship gives me a renewed sense of community at exactly the right time, and that’s been very helpful.

But I’d say it goes beyond community. As I mentioned, some Junior Fellows are now mentors for Científico Latino. I am truly grateful for their interest and enthusiasm in helping these young scientists succeed. There are many Junior Fellows whom I now consider part of my family.