Cracking a Mystery of Massive Black Holes and Quasars with Supercomputer Simulations

At the center of galaxies, like our own Milky Way, lie massive black holes surrounded by spinning gas. Some shine brightly, with a continuous supply of fuel, while others go dormant for millions of years, only to reawaken with a serendipitous influx of gas. The details about how gas flows across the universe to feed massive black holes remain a big question.

A new paper published August 17 in The Astrophysical Journal addresses some of the questions surrounding these massive and enigmatic features of the universe by using new high-powered simulations.

“Supermassive black holes play a key role in galaxy evolution, and we are trying to understand how they grow at the centers of galaxies,” says study lead author Daniel Anglés-Alcázar, an associate research scientist at the Flatiron Institute’s Center for Computational Astrophysics (CCA) in New York City and an assistant professor of physics at the University of Connecticut. “This is very important not just because black holes are very interesting objects on their own, as sources of gravitational waves and all sorts of interesting stuff, but also because we need to understand what the central black holes are doing if we want to understand how galaxies evolve.”

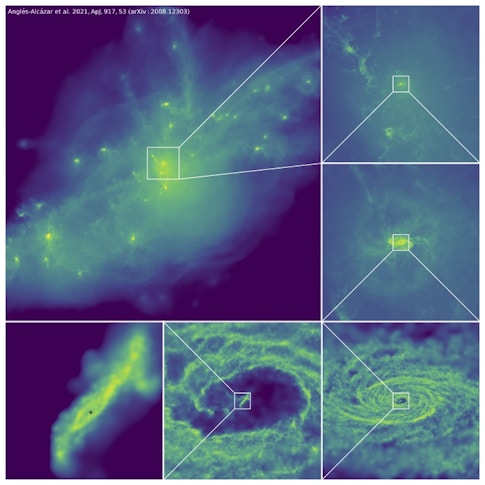

Anglés-Alcázar says a challenge in answering these questions has been creating models powerful enough to account for the numerous forces and factors that play into the process. Previous works have looked at black holes at either at very large scales or the very smallest of scales, “but it has been a challenge to study the full range of scales connected simultaneously,” he says.

Galaxy formation starts with a halo of dark matter that dominates the mass and gravitational potential in the area and begins pulling in gas from the surroundings, explains Anglés-Alcázar. Stars form from the dense gas, but some of it must reach the center of the galaxy to feed the black hole. How does all that gas get there? For some black holes, this means huge quantities of gas, the equivalent of ten times the mass of the sun or more, are swallowed in just one year, says Anglés-Alcázar.

“When supermassive black holes are growing very fast, we refer to them as quasars,” he says. “They can have a mass well into one billion times the mass of the sun and can outshine everything else in the galaxy. How quasars look depends on how much gas they add per unit of time. How do we manage to get so much gas down to the center of the galaxy, close enough that the black hole can grab it and grow from there?” The new simulations provide key insights into the nature of quasars, showing that strong gravitational forces from stars can twist and destabilize the gas across scales and drive sufficient gas influx to power a luminous quasar at the epoch of peak galaxy activity.

In visualizing this series of events, it is easy to see the complexities of modeling them, and Anglés-Alcázar says it is necessary to account for the myriad components influencing black hole evolution.

“Our simulations incorporate many of the key physical processes — for example, the hydrodynamics of gas and how it evolves under the influence of pressure forces, gravity and feedback from massive stars. Powerful events such as supernovae inject a lot of energy into the surrounding medium, and this influences how the galaxy evolves, so we need to incorporate all of these details and physical processes to capture an accurate picture.”

Building on previous work from the FIRE (“Feedback in Realistic Environments”) project, Anglés-Alcázar explains a new technique outlined in the paper that greatly increases model resolution and allows for following the gas as it flows across the galaxy with more than a thousand times finer resolution than previously possible.

“Other models can tell you a lot of details about what’s happening very close to the black hole,” he says, “but they don’t contain information about what the rest of the galaxy is doing — or even less, what the environment around the galaxy is doing. It turns out it is very important to connect all of these processes at the same time. This is where this new study comes in.”

The computing power is similarly massive, Anglés-Alcázar says, with hundreds of central processing units (CPUs) running in parallel that could have easily taken the length of millions of CPU hours. The resource-intensive simulations were possible thanks in part to the Flatiron Institute’s high-performance computing facilities, he says.

“This is the first time that we have been able to create a simulation that can capture the full range of scales in a single model and where we can watch how gas is flowing from very large scales all the way down to the very center of the massive galaxy that we are focusing on,” he says.

For future studies of large statistical populations of galaxies and massive black holes, we need to understand the full picture and the dominant physical mechanisms for as many different conditions as possible, says Anglés-Alcázar. “That is something we are definitely excited about. This is just the beginning of exploring all of these different processes that explain how black holes can form and grow under different regimes.”

In addition to Anglés-Alcázar, the study includes authors from the FIRE and SMAUG (“Simulating Multiscale Astrophysics to Understand Galaxies”) collaborations: Eliot Quataert of the University of California, Berkeley, and Princeton University; Philip Hopkins of Caltech; Rachel Somerville of the CCA; Christopher Hayward of the CCA; Claude-André Faucher-Giguère of Northwestern University; Greg Bryan of Columbia University and a visiting scholar at the CCA; Dušan Kereš of the University of California, San Diego; Lars Hernquist of Harvard University; and James Stone of the Institute for Advanced Study.

For more information, please contact [email protected].